Welcome to our new The Exclusive deep dive content about our Latin American ecosystem. We’re giving our registered newsletter users a sneak-peek of these soon-to-be paid for articles.

Contxto—Politics, football, and Tesla’s current stock price all have one thing in common with SoftBank—Latin America’s largest foreign investor—; you should never mention them in conversation unless you’re ready for chairs to start being thrown around.

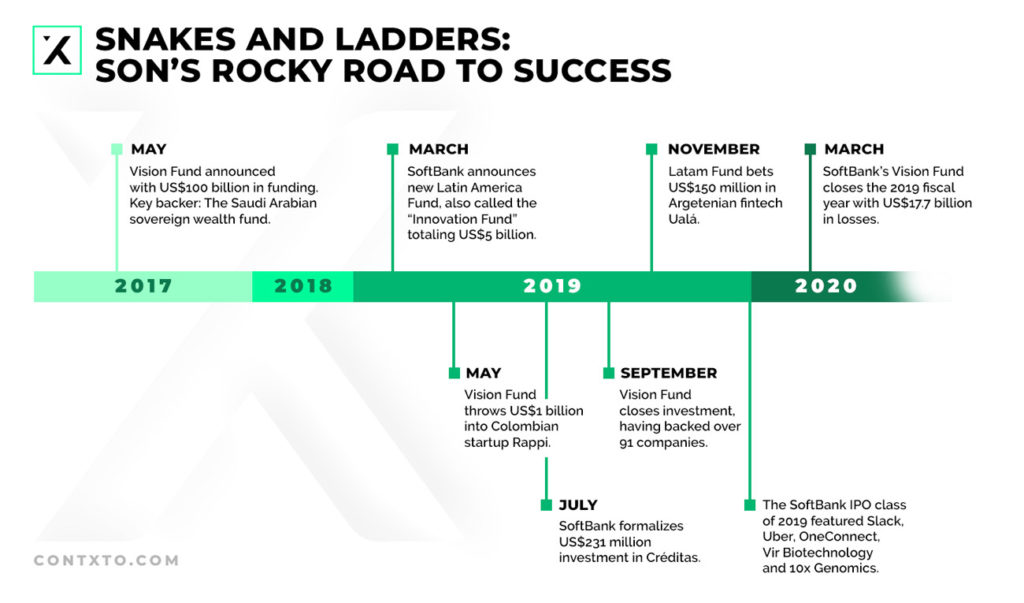

Masayoshi Son—SoftBank’s founder and CEO—has been a firm believer in technology and its dominating role in humankind’s future since before the pop of the dot com bubble. He recently made a name for himself by putting together his infamous US$100 billion Vision Fund to invest in tech-oriented startups around the world.

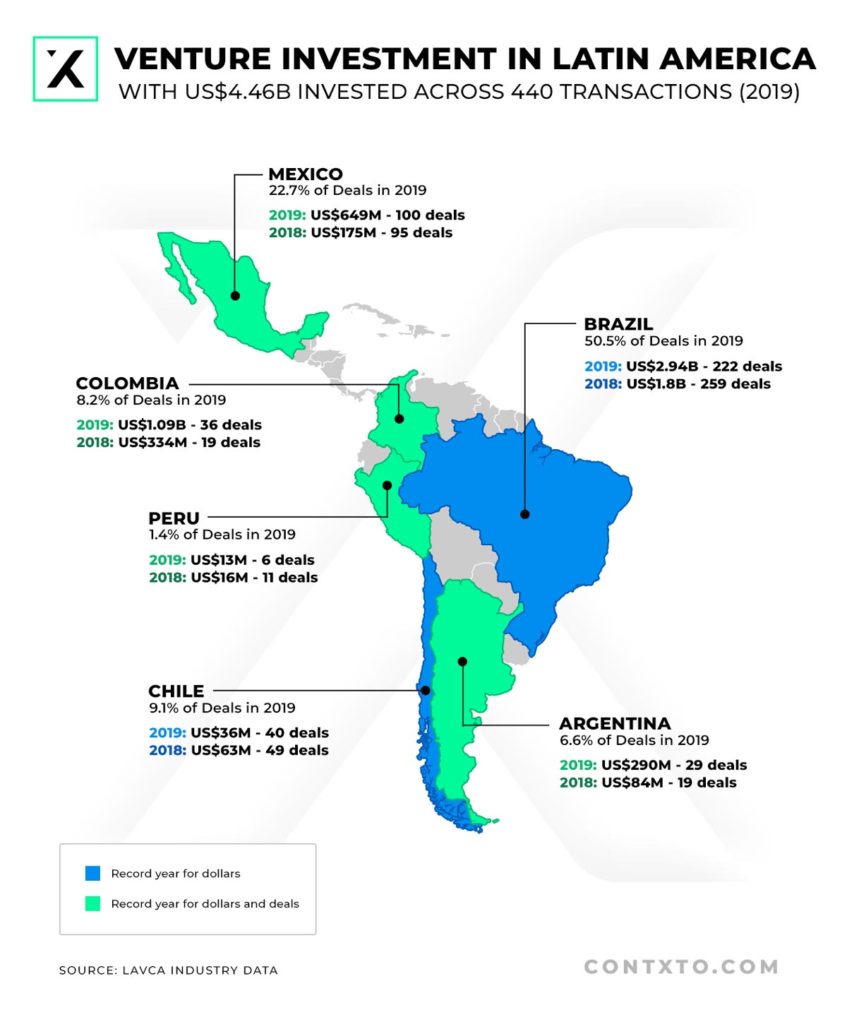

Last year, Masa—as Masayoshi Son is affectionately nicknamed by the press—announced the launch of a US$5 billion fund geared exclusively towards Latin American startups. This may sound measly next to the Vision Fund’s gargantuan US$100 billion, but consider that the total amount invested by VCs in Latam last year was US$4.6 billion.

How does that US$5 billion sound now?

An investment of this magnitude is bound to uproot the nature of the emerging tech landscape in the region, but there’s one industry that will be specially transformed: fintech.

Because fintech companies need relatively higher investment tickets to take off, the implications of the so-called Latin America Fund are going to be decisive for the Konfios and Clips of the region.

Son’s bets could propel the Latin American fintech landscape into stardom, or they could end up inflating company valuations to the point where they would act as a goad for a price war between key players.

Will Masayoshi Son’s risk addiction make fintech Latam’s crown jewel, or will it push its players into a deadly cockfight?

Gigantic piles of Japanese money—what could possibly go wrong?

Foreign money is always exciting, especially for an attention-hungry region with enormous potential like Latam—but I wouldn’t start celebrating just yet. There is one case which reveals the possible dangers of Son’s investment invasion: Uber, Rappi and DiDi’s SoftBank-funded fight.

Venture capitalists don’t regularly back competing companies in order to avoid cannibalizing their returns.

Arguments can be made for backing more than one player, but it’s normally done at an early stage and in small amounts as a hedge. If one of the companies fails, the VC’s losses should be compensated by a rival shining through.

However, SoftBank has taken this to an extreme. The Japanese group has written blank checks to direct competitors, incentivizing them to fight each other aggressively for sales.

The Japanese group invested US$1 billion in Rappi, US$1.6 billion in DiDi, and became Uber’s largest shareholder after it’s IPO, all in 2019.

According to a Wall Street Journal report, this strategy has fueled a price war in the food delivery industry in Latam. Uber, DiDi, and Rappi used their newly found deep pockets to claw at each other’s throats.

Son’s intention is to create a “cluster of #1s” in the region. He believes the Latin American market is large enough to support various big players.

However, the WSJ report points to a huge backfire in the strategy: SoftBank money is pulling startups’ focus away from growth at a stage where their top priority should be establishing a path to profitability.

If SoftBank hasn’t learned from the Vision Fund’s failures, these kinds of clashes could permeate the tech scene as the Latin America Fund begins to give companies capital.

Fintech on the frontlines

There are two reasons why Son’s investment will wreak chaos in the fintech industry especially.

First off, because fintech is more expensive to set up than other types of startups, the cash poured in by SoftBank will cherry-pick the region’s top players.

The second reason is that, because of Latin America’s history of financial instability, a bad bet resulting in a challenger or even a neo-bank’s bankrupcy could set the region back decades in embracing fintech.

Buying kingship: Masa’s money could determine Latam’s fintech ruler

The first rule about setting up a fintech is… you need money. Despite the fact that digitalization helps lower some of the starting costs, the reality is that, in order to operate a fintech, you need the financial regulator’s blessing—and that blessing will cost you.

Fintech regulation isn’t consistent across the region, but the general trend is that financial authorities are beginning to define their stance on new industries like crowd-funding, blockchain, and digital currencies.

An IMF working paper highlights Mexico publishing its Fintech Law in 2018, Brazil’s National Monetary Council issuing a new resolution giving fintech firms the opportunity to enter the financial market, and the Colombian government working on a framework for crypto-assets as some key developments.

Disparities and inconsistencies across the region allow for some countries to have cheaper costs of setting up a peer-to-peer lender, for example.

In Brazil, the central bank set minimum capital requirements for P2P lenders at BRL$1 million (~US$175,000), while Mexico established a US$250,000 minimum. Colombia, on the other hand, lowered the requirement down to US$50,000.

All in all, fintechs are much more costly to build than other kinds of startups, which is why getting proper funding is imperative for their growth. With SoftBank being the most important source of capital, fintech scouted by Son will have an enormous advantage over other players, making it hard for them to blossom—or even sprout.

To top it all off, because digital banks tend to have strong network effects and sticky customer bases, early stars are likely to keep their dominance of the markets for years to come.

SoftBank could accidentally undermine fintech

Even SoftBank’s most powerful investments have been known to sour. The Vision Fund posted a US$17.7 billion loss for the year ended in March 2020, nearly half of which came from only two companies. Son said in a Forbes interview that he predicted Covid-19 to bankrupt 15 of his investments.

Despite the fact that those losses came from companies outside Latam, the track record is worrisome. If a fintech were to suffer a similar fate, Latin Americans could be spooked into trading their challenger bank account for a “safer” legacy bank option.

Latin American countries are either in the middle of, or have a troubled history with, financial instability. Argentina still has inflation upwards of 40 percent. Mexico’s peso has experienced a triple-digit depreciation since 2009. Uruguay’s 2002 banking crisis skyrocketed unemployment to more than 16 percent.

The pandemic has just made matters worse, pushing growth rates to historic lows.

This rocky financial history makes the average Latin American have something similar to a PTSD episode every time someone mentions bank runs or debt crises.

Since fintech penetration is still in its early stages, a risky bet on behalf of SoftBank resulting in the bankruptcy of an inflated digital bank could scare people away from embracing alternative financial channels.

Son’s gambles in Latin American fintech could result in a bad headline or two for SoftBank, but it could set back the adoption of fintech in the region back years.

The sunny side of Son’s bet

Dramatic outcomes aside, not everything Masayoshi Son touches will rot. The much-needed growth of Latin America’s underfunded VC industry is likely to spur a new wave of exciting startups, and the strategy SoftBank is laying out is radically different than that of the Vision Fund.

According to one insider, SoftBank is partnering with local VCs in order to break into the Latin American market. Andre Maciel revealed the reasons behind the friendly outreach in an interview with Bloomberg in late 2019: the whale that is the Latin America Fund doesn’t have the know-how, time, or network to comb through potential small Latam startups.

By fostering innovation in the region through various channels, SoftBank waters the seeds of startups too small for the Latin America Fund until they are large enough to warrant the fund’s backing. SoftBank has reportedly said it has a US$100 million minimum, so helping firms get to that point will accelerate the pace of its investments.

Masayoshi and his Bolivian COO, Marcelo Claure, have already begun to coordinate investment strategies with Valor Capital, a Brazilian VC firm with four funds focused on both Brazil and the US, and Argentina’s Kaszek Ventures.

Results from these first friendships have already begun to peek through: Valor Capital’s prized company, Gympass, received US$300 million from SoftBank soon after they joined forces, while Kaszek and the Japanese fund jointly invested US$17.8 million in Volanty.

SoftBank plans to invest another US$500 million in another 10 local funds in the upcoming months.

However, there might be pushback from the established venture capitalists in the region.

Partnering with a gigantic Japanese conglomerate that could strike you out of the market in the blink of an eye seems a lot like making a deal with the devil. To be fair, I’d be terrified if I were getting in bed with a docile-looking Japanese guy who’s net worth is one-tenth of my country’s GDP.

A quick number to put this into perspective: Colombia saw a total of US$1.09 billion of venture capital investments across 36 deals in 2019. SoftBank’s backing of Rappi accounted for US$1 billion of that total.

Monashees—a Brazilian VC fund who was an early investor in the fintech Neon and the bike rental app Yellow—declined SoftBank’s partnership offer.

SoftBank Latin America fintech venture: An expensive coin toss

SoftBank has made its name on being a disruptor—and it’s bound to disrupt the Latin American fintech industry in the following years.

Son’s intervention will be particularly important for the fintech sector and could be a decisive move in the mainstream adoption of classic fintech models like P2P lending, crypto-currencies, or payment processing.

By potentially solving two of fintech founders’ largest concerns (access to funding and scalability), he could transform the region in the long run.

If Son has been at all humbled by his losses and missteps in the Vision Fund fiasco of 2019, this could mean that fintechs in the region are about to experience massive growth.

On the other hand, if he refuses to follow the advice of his Bolivian COO and local VC partners, his failures could leave a lasting scar on the sector’s skin.

-NS