October 5, 2020

Contxto – Some might think that the story of fintech in Latin America is that of an underdog: A rebellious bunch of disruptors playing by their own rules and trying to conquer a game as old as time. However, the most recent strategy adopted by challenger banks doesn’t portray them as dissidents – in fact, it’s anything but.

Latin America’s challenger banks are betting on plastic.

This might seem like a shot in the dark at first but, when you think about it, this relatively new direction is intuitive. By making Latin America’s young, connected, and credit card-averse population feel less intimidated by traditional financial products, contenders have fast-tracked their way to success.

You might be tempted to ask what makes challenger banks any more likely to succeed than the legacy banks. The traditional outfits, on top of having a larger network and deeper pockets, are veterans in the credit card business.

The answer is two-pronged. First, challengers have understood something about Latin American demographics that traditional banks have ignored. Second, the size and nature of the market leaves enough room for a new, slightly different model to be profitable.

Traditional banks have a track record of squeezing every penny out of their clients, making their accounts unattainable for most. Challenger banks, on the other hand, have eschewed these practices, attracting clients who previously thought of themselves as “unworthy” of credit.

We all know the story: Latin America’s fees, commissions, and interest rates on credit cards walk a thin line between “onerous” and “usury”. The countries in the region with the highest rates in 2018 (Brazil and Argentina) had APRs well into triple digits.

By contrast, in Europe cards can have APRs as low as 16 percent, according to ECB data.

The stratospheric costs, coupled with undependable customer service channels and lengthy application processes alienated most of the population. By instrumenting policies that legacy banks thought were reducing the risk in their wallets, they actually ended up shooting themselves in the foot.

The Santanders and BBVAs of the region made most of their potential clients feel overwhelmed by the idea of acquiring a credit card—or even a bank account, for that matter.

If we look at data from a financial inclusion survey put together by Mexico’s INEGI, we can see a pattern take shape.

When asked why they didn’t own a credit card or bank account, over 30 percent of those surveyed stated that they either didn’t think their income was sufficient, or sufficiently stable, to warrant having one.

A quarter of respondents claimed that they didn’t think they needed a bank account or a credit card at all.

Some of these numbers are, no doubt, explained by poverty levels across the region.

However, I believe the story here goes much deeper: People across Latin America have been told that they are unworthy of credit. Traditional banks have, in the eyes of the general population, formed an elite club which only grants memberships to the richest or most educated.

Here’s where fintech swoops in. Armed with flashy, neon colored marketing, challenger banks are trying to penetrate the huge Latin American market by catering to a younger demographic. A demographic, which by the way, is the second largest in the world: After Africa, Latam has the highest percentage of young adults in the world.

If we look at the value proposition of the up-and-comers, they focus on three main things:

Indeed, focusing on a digital strategy could narrow their target market, but this may be the right strategy to pursue. After all, smartphone penetration in the region is projected to reach 73 percent by 2025. Furthermore, a McKinsey payments report tells us that client segmentation is the best way to secure increased profitability in the future.

By giving customers a physical credit card to compliment their online proposal, challenger banks are offering a feeling of belonging that the incumbent banks have denied.

This feeling of belonging could also be achieved through handing out debit cards, which act as an initial, compromise-free alternative to a credit card that banks can use to strap customers in. Once customers have tested the financial waters, challengers should be able to seduce them into acquiring the fancier, more lucrative credit card.

In other words, challenger banks are sticking it to the man… by becoming a better version of him (or her).

When I hear that banks are acquiring younger, lower-income clients that traditional banks have turned down, alarms start flashing in my head like there’s about to be an earthquake. Won’t these clients inflate the risk taken on by these challenger banks? Shouldn’t this additional risk be compensated with higher, not lower, fees, and interest rates?

The (unfortunately trite) answer to this question is ‘it depends’.

Of course taking on risk irresponsibly results in larger default ratios, but there have been success stories of fintechs implementing less restrictive strategies with success.

Take Creditas, for example. In 2017, less than 1 percent of the loans issued resulted in default, with that number predicted to rise to 2 percent in 2018. However, the verdict is still out on whether these statistics are unique to Creditas or rather a regional standard, and whether they will be replicable in credit card-based projects rather than loans.

Making plastic a part of their portfolio may seem contradictory for challenger banks, but it actually makes perfect sense. By getting in bed with physical credit cards, challengers are capitalizing on Latin America’s largest source of bank revenue.

There are plenty of reasons why fintechs might want to stay away from issuing cards. The regulatory burdens of being a financial institution allowed to do so are taxing; the application process alone might be enough to deter some contenders.

Operating under a fintech license or permit, especially given recent changes in regulation, could allow companies to keep growing without being swamped by governmental controls. Credit institutions (AKA banks) are heavily supervised by central banks and financial regulators in order to safeguard their clients’ money and the country’s financial stability.

Fintechs, on the contrary, enjoy lax, sometimes even non-existent, regulations. In Mexico, for example, fintechs are normally registered as “Technological Financial Institutions” (ITFs), which are far less strictly overseen than banks and have lower minimum capital requirements.

On top of that, the process to apply for the permits necessary to issue credit cards is expensive. In Mexico, applicants can rack up costs upwards of MX$3 million (~US$135,000) just to be considered—not counting capital requirements.

So, why are challengers emitting credit cards left and right? The trend has been picking up speed in late 2020. Ualá launched its first credit card outside of Argentina in September and Kapital offered its first fully Mexican credit card for the first time in August.

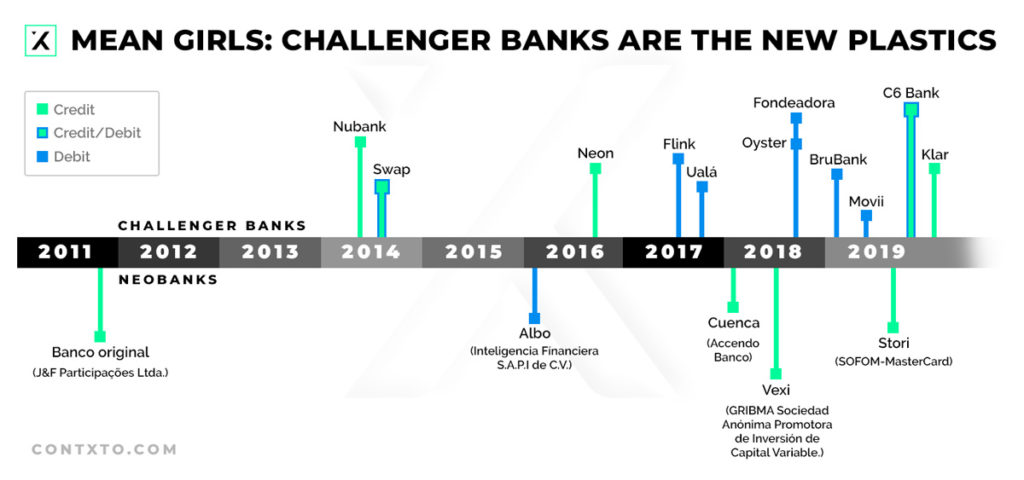

The revolution really started, though, when Nubank’s first card was launched all the way back in 2014, a year after it was founded.

Nubank’s success is what perked up the ears of competitors. The challenger currently has over 30 million customers, it is valued at over US$10 billion, and its primary product is—you guessed it—a credit card.

McKinsey has described Latin America’s banking revenue to be “credit card and liquidity driven”. This means that the main revenue sources for financial institutions in the region are credit cards and interest income from overdrafts.

Remember the jaw-droppingly high credit card costs we mentioned earlier?

Despite being obscenely high, customers had virtually no other choices, and so continued to shell out cash to the legacy banks. The retail banking market in Latam had operated as an oligopoly, with banks agreeing to artificially raise account costs when there was no risk to justify it.

Nubank is evidence that cutting the costs of incumbent’s products can still be profitable, and the key, I suspect, is all in the interchange fees (the fees vendors’ banks must pay every time a customer makes a purchase with a card). If we look at the challenger-emits-credit-card business model from a global standpoint, we can see why.

While challenger banks which have emitted credit cards in Europe are currently struggling to survive, similar models in Latin America and the U.S. are booming.

Revolut laid off 62 employees in what was a bit of a scandal in June, and Monzo was set to lay off 120 employees in the summer. Konfio, on the other hand, just received US$58.8 million in funding, and Nubank raised US$300 million in June.

Interchange fees in the EU dip well below half a percent, while those same fees average around 2 percent for South and North America… spot a pattern? The inflated industry averages for credit card costs make it possible for challengers to make money while stealing market share from traditional banks.

So, it seems that big banks have made two important mistakes here:

First, they alienated customers that fintechs then picked up to build their own client base.

Next, they charged so much for their products that they left the market primed for a cost cutting strategy. This allowed the challengers to charge near zero or zero fees on most items and still remain profitable.

Way to trip yourself up, guys.

However, demand isn’t the only thing driving the credit card wave. Visa and Mastercard’s recent strategies are placing a huge bet on fintech in order to remain relevant.

According to a report by S&P Global, these two giants have both turned their attention towards alternatives to their regular business lines, choosing to back or acquire existing companies rather than build their own.

Despite branching out to other business segments in 2020 (think Visa buying Plaid and investing in Square), 95 percent of the payment processors’ revenue still comes from just that: Payment processing.

According to Mastercard’s own research, digital purchases are becoming ever more relevant. E-commerce as a share of total retail sales has been on the rise, and has climbed up to 22 percent in the US and 33 percent in the UK in recent months due to the pandemic.

In Latin America, the e-commerce industry is currently only 4.2 percent of total retail sales, but is expected to double its value by 2022. Not only that, but the primary digital payment method is, with a whopping 52 percent share of the total, the credit card.

Allying themselves with the likes of Nubank and Konfio, Mastercard and Visa are able to access demographics who are more likely to make purchases online, and who are willing to make those cards their primary spending vehicles.

Forming relationships with the banks who are likely to serve the world’s future generations secures a significant portion of their future consumer base.

Don’t start calling your bets just yet, though. Challenger banks are likely to face fierce competition from traditional banks trying to implement digital strategies and their neo-bank spinoffs.

If challengers’ business models are too focused on luring in customers, they might miss their profitability mark entirely. If challengers get carried away in persuading new clients to join their ranks, offering them discount after discount, they might lose out on the share of profit they were trying to tap into in the first place.

Despite the more elevated costs and regulatory burdens of being a financial institution, profit margins on credit cards are so large and tapping into the market would have such growth potential, that a cost-cutting strategy isn’t only viable, it’s commendable.

All in all, if challenger banks manage to boost the confidence of the millions of Latin Americans who have been kicked down by big banks, steering them towards their easy to acquire credit cards with upbeat designs and apps to accompany them, they should be able to propel their growth to new heights.

Yet, offering zero commissions on most operations for their account holders can be a valuable strategy if implemented correctly.

But, as always, having a sound business model is what will tell apart the fleeting shooting stars from the scene’s future big players.

-NS

Por Santiago Cardona

March 4, 2026

Por Yanin Alfaro

February 17, 2026

Por Israel Pantaleón

February 17, 2026

Por Stiven Cartagena

February 13, 2026